The Indexation Clause – otherwise referred to as the Stability Clause, Inflation Clause, or Severe Inflation Clause (SIC) – is designed to maintain the real monetary value of the retention and (where applicable) the limit under a long-tail excess of loss (XL) reinsurance treaty over the duration of the claims payout pattern. The clause is only relevant to losses that are of a long-tail nature (i.e., that take a long time to become paid) and is commonly found in the terms and conditions of Motor Liability (MTPL), General Liability (GTPL), and Professional Liability TPL XL reinsurance contracts of European cedants.

The term “Stability Clause” (used mostly in France) indicates most succinctly the perceived main purpose of the clause, which is to maintain a stable relationship between the reinsurance retention and the reinsurance limit, and to ensure that the relative proportion of loss distributed between the reinsured limit and retention would stay the same. However, on an unlimited Motor XL treaty, the clause really only works in favour of the reinsurer, since there is no specific reinsured limit to be indexed. The clause seldom works in favour of the cedants of GTPL and Professional Liability portfolios, because these cedants have no need for an indexed reinsurance limit, as the underlying liability policy limits are not indexed.

Indexation Clauses came into general use in European long-tail XL treaties in the 1970s, having first been used in French unlimited MTPL XL contracts following the move away from the old Napoleonic principle of nominalism (“le franc égale le franc”), in a ruling of the Cour de Cassation in 1957. Despite now being an omnipresent feature of European long-tail treaties, Indexation Clauses are often misunderstood and seldom studied in the depth required to assess their ultimate financial effects on the contractual relationship etween reinsurer and reinsured.

Depending upon the wording of the Indexation Clause, the adjustment of the reinsured retention can have a significant effect on the amount of a claim that the reinsured can recover from the reinsurer. Several variations of the clause are in use. Differing market practices in different legal regimes have influenced the way that these clauses have evolved, but all too often the XL reinsurance contract is concluded without proper attention being paid to the financial effect of the Indexation Clause. Cedants need a full understanding of the financial effect of the clause to make a proper estimation of the ultimate level of their non-proportional long-tail reinsurance recoveries, in order to meet the increasingly demanding requirements of both regulators and rating agencies.

What Are the Different Versions of the Indexation Clause?

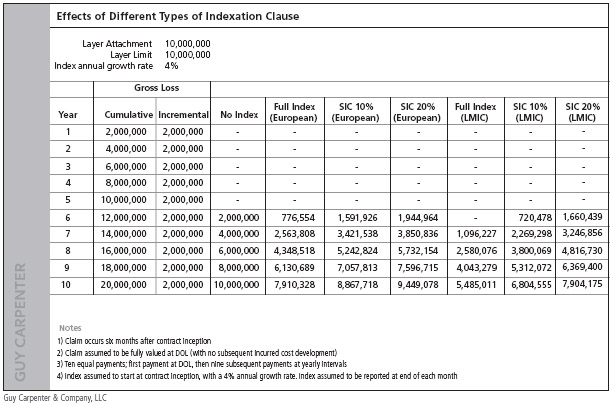

Guy Carpenter conducted a detailed analytical study of the main variants of the European Indexation Clauses currently being applied in the reinsurance market. There are two basic types of clause now in circulation: the European Index Clause (EIC) and the London Market Indexation Clause (LMIC). The former applies the index at each date of payment and therefore distributes the effect of inflation in line with the payout pattern of the claim. The latter, by contrast, traditionally indexes the total value of the claim at the date of final settlement. This means that the retention is likely to be revalued at a substantially higher level than with the European version of the clause.

The reason the LMIC is structured differently is to reflect the usual practice of lump-sum third-party bodily injury liability settlements in the UK.With the advent of the periodical payment order (PPO) introduced by the UK Courts Act of 2003, a new rider has been introduced into the LMIC clause to allow for European-style application of the index at the date of each partial payment, although this is only applicable to PPO cases.

The SIC clause is a variation of the LMIC or the EIC, according to which the index only starts to increase excess of a given percentage, which may be any value between 10 percent and 60 percent, subject to negotiation of the contract. In a low inflationary environment, where most claims are settled within 10 years, an SIC clause of 30 percent will in practice mean that the reinsurance contract is not indexed. A Franchise Inflation Clause differs from the SIC in that it applies the full value of the increase in the index since the base date once the stated margin has been breached, with a franchise of 10 percent. As soon as the index exceeds 110 relative to the base value of 100 at contract inception, the retention is adjusted by the full value of the increase in the index since the base date, and all recoveries will be reduced accordingly.

The table below lists the versions of the Indexation Clause typically used across European countries. Beyond the basic splitting of clauses into “EIC” or “LMIC” generic types, there are five operational variants, and many further variations of these are possible in terms of:

- The percentage level of the franchise or excess margin

- The choice of the base index (for example, the country Retail Price Index (RPI) or the salaries and wages of all or specific employee groups)

- The date at which the base index starts working

The amount of the expected recovery from long-tail XL reinsurance treaties of course will vary in line with the differing provisions of these clauses. The table and chart below illustrate how the different types of Indexation Clause (based on a projected European salaries and wages index averaging 4 percent annual compound growth) would affect the amount recoverable from the amount of EUR10m xs EUR10m that would have been theoretically recoverable with an unindexed retention:

Why Is There No Indexation Clause in US Casualty Treaties?

It is perhaps surprising that in the United States – the legal environment with arguably the greatest historical claims inflation problem – casualty XL reinsurance treaties do not even contain an Indexation Clause.

The reason for the absence of an Indexation Clause in the US market goes back to the strong resistance of US domestic insurers to its threatened introduction back in the 1970s and 1980s. The argument at that time was that RPI growth in the United States was insignificant, such that the introduction of an Indexation Clause – especially an SIC with a 50 percent or 60 percent franchise or excess – would have been meaningless. Moreover, there was no interest from cedants to have the benefit of an indexed reinsurance limit, since the original policy limits were not indexed. The US reinsurance market opted instead to concentrate on other clauses to protect itself from inflationary exposure; for example, through the introduction of the claims-made trigger and the sunset clause.

Is the Indexation Clause Showing the Intended Results?

The Indexation Clause is primarily designed to protect the position of the reinsurer against bearing an over-proportional amount of the inflation-driven increase in a claim that is subject to an XL recovery. The current situation with bodily injury claims inflation in many European territories is that the Indexation Clause is doing only part of the job it was intended to do.

In certain territories, most notably the UK and France, the inflationary pressures on bodily injury claims go beyond those purely economic factors reflected in the RPI, salaries and wages index, or industrial price index. Additional social inflationary pressures have arisen through new legislation (e.g., the “tierce personne” ruling in France) or by the decision of a judge, as in the case of Thompstone v Tameside & Glossop Acute Services NHS Trust (2006), to link the periodic payments in respect of future care, not to the standard RPI index, but to the ASHE 6115 Index (reflecting the movement in weekly earnings for care assistants and home carers). The Indexation Clause cannot sensibly reflect the full extent of these inflationary pressures.

Conclusion

In a number of European territories, the Indexation Clause does not reflect the full extent of inflationary pressures on the size of complex third-party bodily injury claims, especially those involving long-term disability with a 24-hour care requirement. This is an especially sensitive point, given the trend to increasing XL treaty deductibles, above which only the more complex type of bodily injury claims are likely to attach. To alter the base index to reflect these new inflationary factors on the bodily injury part of large claims would, however, not be an equitable solution for the reinsured without an appropriately larger discount for the reduced projected cash flows from the XL reinsurance contract. This requires a robust analytical approach to the assessment of the impact of the Indexation Clause, with a strong technical understanding of the impact of variations in the wording of the clause.