The impacts to society from changes in longevity and life expectancy will be wide-ranging and incredibly difficult issues to grapple with. A 2012 International Monetary Fund (IMF) study revealed that if individuals lived three years longer than expected the cost of aging could increase by 50 percent.

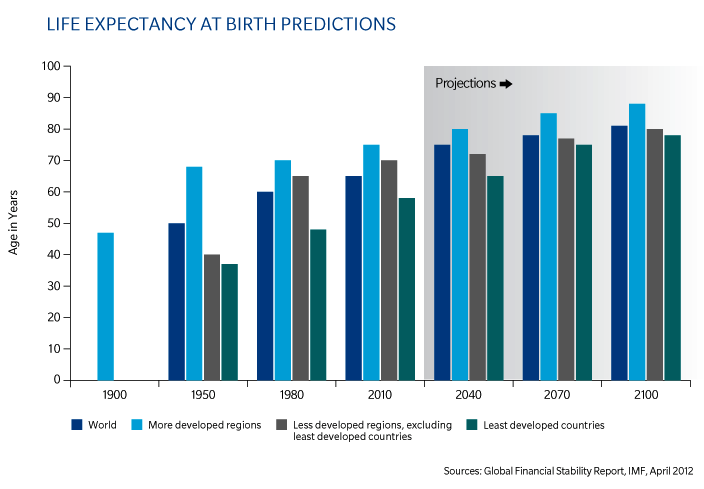

This translates to 50 percent of 2010 gross domestic product (GDP) in advanced economies and 25 percent of 2010 GDP in emerging economies. Globally that amounts to tens of trillions of US dollars. The United Nations expects the aggregate expenses of the elderly will double over the period between 2010 and 2050. The figure below shows the projected trend of rising life expectancy to continue in all regions of the globe regardless of economic advancement.

For (re)insurers, increased longevity creates very specific risk, as improvements are notoriously difficult to measure and to forecast. Diversification is challenging if not impossible. For traditional life insurance with death benefits, mortality improvements have been positive for the industry - for both (re)insurers and consumers. However, with an aging population, insurance buyers are transitioning to products with living benefits - annuities and disability insurance to protect income streams and long-term care and critical illness coverage to help meet the expenses of aging and morbidity. For these products, inaccurate estimates of longevity change the economics of the business in significant and potentially overwhelming ways. Mortality and longevity risk are often considered to hedge each other, but the underlying populations are so different that it is difficult to translate that hedge into real risk mitigation.

To illustrate the propensity to underestimate longevity, consider the extreme examples of two defunct insurance markets - the viatical settlement market and stranger-owned life insurance (STOLI). Viaticals were formed to buy policies at a discount from face value from AIDS victims, effectively transforming life insurance policies into living benefits. The viatical had to pay a premium until the policyholder's death and would then make a profit. But due to the innovations in treatment and drug therapies, victims lived much longer than previously expected and virtually all viatical settlement companies eventually went out of business. STOLI investors bought new policies on behalf of groups specifically chosen to have higher mortality than life (re)insurers anticipated in their pricing. Despite this selection, almost all STOLI portfolios performed much worse than expected, losing millions of dollars. These were both speculative businesses, but highlight how difficult longevity risk is to anticipate - even when it is the primary risk specifically underwritten.

Though longevity risk has been a persistent industry issue, we identify it as an emerging risk for two main reasons:

- The persistent low interest rate environment is magnifying the impact of longevity risk for long-term coverages and,

- Many (re)insurers will increase their longevity exposure dramatically over the next several years as consumer interest in lifestyle products grows and as pension liabilities are transferred to the insurance sector.

Traditional actuarial forecasting methods extrapolate historical trends into the future, taking into account known changes between the study base and the projected cohort. This has proved adequate for mortality studies, as underlying decreases in mortality have helped projections be sufficiently accurate for death benefit projections, pricing and reserving. For longevity studies, however, that approach, applied simplistically, is practically useless. A more granular method, evaluating the several leading causes of death and their changes over time, taking into account different rates of change by age, gender, risk profile, and several other factors, is better, but still very problematic for reliable modeling.

One reason that modeling is more challenging for longevity risk than mortality risk, is that the quantum events that can move mortality higher (war, pandemic, global catastrophe) are avoided by mankind if possible and, if they happen, still only have a brief impact. The impacted population then typically experiences a long period of recovery, potentially with even lower mortality rates. The events that can move mortality lower in a quantum way (new vaccines, cures for diseases, improved surgical outcomes, greater public safety measures) are highly sought after and, once obtained, create permanent, lasting change in long-term mortality. This drive to survive and thrive is well illustrated by the recent and ongoing shifts in US medical expenses - another important emerging threat.