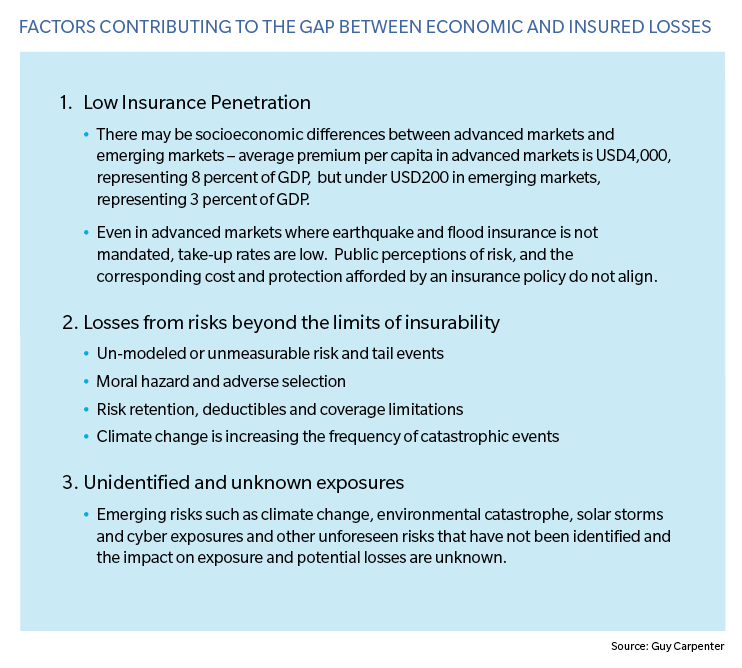

There are a number of factors that contribute to the gap between economic loss and insured loss and as new risks emerge such as climate change and political risk, this gap will only continue to widen.

The cost of uninsured events frequently falls on governments through disaster relief, welfare payments or in the form of government bailouts.

By their nature, uninsured risks are rarely explicitly recognized by the ultimate holders of the risk and are not managed appropriately pre-event. An exacerbating factor around certain uninsured risks stems from the lack of exposure measurement and systematic risk mapping, which could provide insight into risk mitigation and risk financing options.

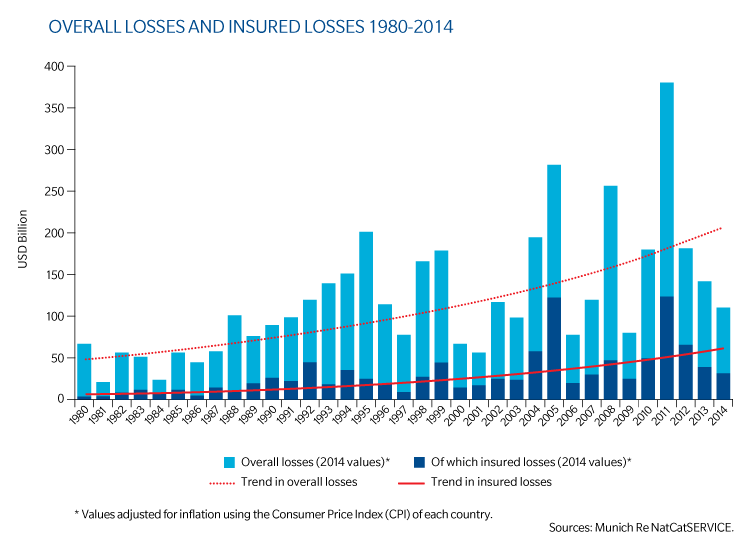

Globally, most funding for hazard mitigation is made available post event, which in turn is coupled with an over-reliance on post-event financing. For example, during the period of 2011-2014 in the United States, the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) granted only USD 223 million in pre-disaster mitigation grants compared to USD 3.2 billion in post-disaster grants (1). Since 2000, globally there has been over USD 1,600 billion in uninsured loss from natural catastrophes (70 percent of total losses) requiring various forms of post-event funding and loss financing or held directly by those impacted (2).

In Europe, The European Union Solidarity Fund (EUSF) was established to provide financial assistance to European Union (EU) countries facing major natural disasters. In the 13 years it has been in existence, the EUSF has paid EUR 3.8 billion (Italy and Germany have received 60 percent of that amount) to supplement the countries' own public expenditures on essential emergency operations. These payments represent 4 percent of the total damage bill and do not include losses to private property, which are assumed to be otherwise insured by private markets. The EUSF encourages risk mitigation but is essentially a post-loss mechanism with finite funding. The exposure beyond the limited financial resources of EUSF, for example, a large event - potentially affecting multiple countries, falls back to the EU countries at a time when their capacity to fund loss is stretched and financial tolerance varies from country to country.

A study by AIR Worldwide indicates that a one-in-100 year earthquake in California could result in USD 75 billion of damage to residential properties. After accounting for insurance take-up, applying deductibles and insurance limits the corresponding estimated insured damage is only USD 9 billion, meaning 88 percent of the loss would be unfunded (3). If an individual's property sustains damage that exceeds the equity in the property (the United States has an average loan-to-value ratio for single family residences that is over 72 percent (4)), that homeowner may simply walk away from his or her home mortgage, shifting the financial burden to lending institutions, primarily the Federal Housing Finance agencies. Without the homeowner to mitigate loss, carry out repairs and continue to make mortgage payments, the ultimate economic loss multiplies. This creates a larger economic problem for the public sector to manage. Despite this exposure to significant loss there is no urgency on the part of public sector entities or lenders to address the matter. As a result, we are left with an environment ripe for greater utilization of private sector monies.

Note:

1. US Government Accountability Office: Analysis of FEMA Data: GAO-15-515.

2. Swiss Re Economic Research & Consulting; Sigma World Insurance Database, 2013.

3. AIR Worldwide: "Twenty Years After Northridge - Can We Fix Earthquake Insurance in California" and "Who Will Pay for the Next Great California Earthquake?" both 2014.

4. Federal National Mortgage Assoc. and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp.: Summary statistics for single family residences at June and July 2015, respectively.